|

|||||||||||

|

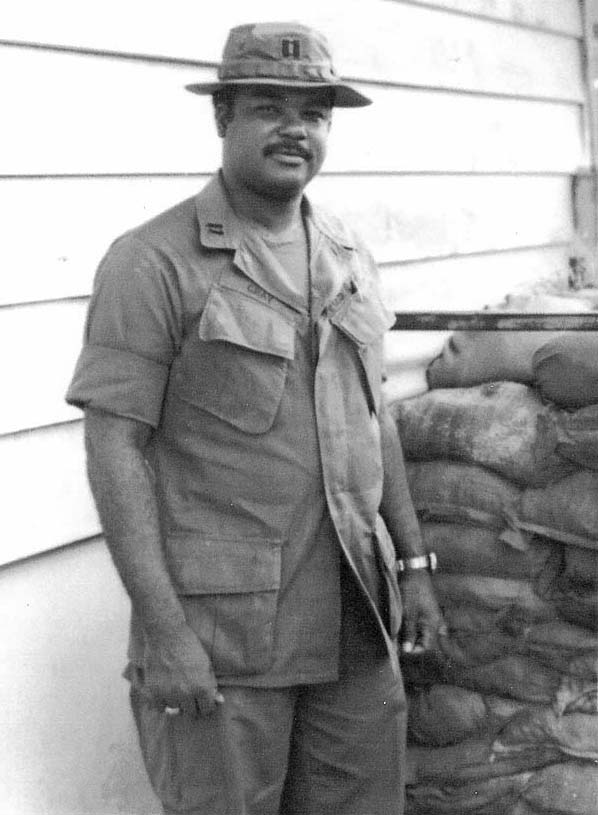

May/June 2013 Quiet Bravery & Focused Effort: BY RICHARD CURREY

“I was undecided,” Gray said. “But, like so many things in life, something happened.” That “something” was a meeting with an Army judge Gray had known in Vietnam. The judge was working with a new initiative at the Pentagon that would mark a sea-change in Army policy: The JAGC wanted and needed more minority lawyers. Making that happen was something the judge thought might interest Capt. Gray. “Out of some 1,600 lawyers serving in the JAGC at that time, only sixteen were black,” Ken Gray said. “And only eight were women. The judge told me the Army wanted to address this lack of diversity.” Gray was invited to join that effort. In October 1971 he started work on this pioneering minority recruitment effort. Gray’s original strategy had several components, including an active relationship with the National Bar Association (the national organization predominantly composed of African-American lawyers and judges) and a nationwide advertising campaign targeting African-American and women law students and lawyers. Gray also came up with an initiative that has remained operational during the forty years since he first pitched the idea: a summer internship program that brings one hundred students from law schools across the nation to spend two months working in JAG offices all over the world. “The internship program was first of all about helping us increase minority recruitment,” Gray said. “But I also knew it would develop ambassadors for the JAGC, one hundred students a year who would go back to their law schools and talk about what we were doing and why a young lawyer might consider coming to work in the Army.” Despite his youth and his relative inexperience as a military lawyer, Gray got the approval for the internship program and saw the funding approved. He is particularly proud that the JAGC Summer Intern Program is still in operation four decades later. And so it was that Ken Gray, one of the Army’s first African-American JAG officers, laid the groundwork for a new kind of JAG Corps, one that embraced and invested in American diversity. But this was only one of many firsts in Ken Gray’s career, both in and out of the Army. From his pioneering recruiting initiative, Gray went on to become the deputy staff judge advocate of the 1st Armored Division and then staff judge advocate of the 2nd Armored Division, the first African American to serve in either capacity. In 1991 he became the first African-American general officer in the history of the JAG Corps when he was promoted to brigadier general, assumed command of the Army Legal Services Agency, and served as the chief judge of the Army Court of Military Review. Two years later he was promoted to major general and sworn in as assistant judge advocate general. Along the way Gray received a Bronze Star and Distinguished Service Medal, among many other awards. Now retired from the Army, Gray is vice president for student affairs at West Virginia University, back on the bucolic campus for a second time in his life. It was here, at the WVU College of Law in the late 1960s, that Ken Gray already had forged diversity and felled racial barriers in a very personal way—by being the only black student in his class and only the third African American to graduate from the WVU College of Law. When I asked Gray to expand on what is clearly a remarkable life, he smiled and said it all started—perhaps a bit improbably—in the tiny town of Excelsior, West Virginia.

Ken Gray hails from the coalfields of southern West Virginia, a territory known for tales of the Hatfields and McCoys and the bloody mine wars of the early 1920s. African Americans are not typically associated with this region or with coal mining and, indeed, their numbers among miners were relatively few. But they were there, and Ken Gray’s father was one of them. “My grandparents lived in Excelsior, too—my grandfather was a Baptist preacher,” Gray said. “The records get a little fuzzy when you hit slavery days, but it’s clear my family goes back many years in West Virginia.” Gray notes that being an only child might have made it a bit easier for his parents to maintain family life without the bite of poverty. “We were certainly not rich, but we made do,” he said. Gray described a childhood in which he was encouraged by his parents and his teachers. “My parents were clear that they envisioned a life for me beyond the coalfields of West Virginia. And my teachers were equally clear that I was college bound.” Gray went on to West Virginia State University, majoring in political science. It was there he was introduced to the Army, in the form of mandatory ROTC participation. “Being in ROTC was required for the first two years of college,” he said. “And I found I liked it.” After four years in ROTC, Gray went on to law school at WVU. “Yes, I was the only black guy sitting in my classes. But an even more immediate test in law school was academic. I had to learn how to study in a more effective way, how to achieve in a setting where the bar was set higher than I’d had as an undergraduate.” Gray went into the Army after he received his law degree in 1969. His first duty assignment was a plum: Ft. Ord, California. “But I was only there eight months,” Gray said. “We had all those guys coming back from Vietnam, and they wanted good duty stations. I was a junior officer, so my turn came when I got orders to the Da Nang Support Command.”

Back home, Gray enjoyed his time with the JAGC minority recruitment effort. It was important work that was making a difference and, aside from that, he was seeing the Army from a different perspective. “I saw that it wasn’t lost on the senior leadership that changes needed to come,” Gray said. “And I saw that many senior officers were willing to try to make those changes happen.” But Gray was still not sure if the Army was the career choice for him. He went from the Pentagon to the JAGC’s Legal Center and School for more training (the “advanced course”). After graduation Gray stayed on as an instructor in criminal law. He was a major by then, had been in the Army nearly a decade, but had still not, he said, “firmly decided I wanted to stay.” But once again, something happened.

Gray accepted the post and found himself sharing oversight of the largest Army jurisdiction in Europe, with ten separate JAG offices spread out across a vast territory. “It was the waning days of the Cold War,” Gray recalled, “and the jurisdiction brought me into day-to-day administration of a very substantial operation, with all the attendant issues, large and small.” Gray next attended the Command and General Staff College at Ft. Leavenworth, and from there was assigned to the 2nd Armored Division at Ft. Hood as staff judge advocate. After three years at Ft. Hood he returned to the Pentagon as chief of personnel and human resources, “in the office where I’d once served as a captain doing minority recruitment.” Gray then went to the Industrial College of the Armed Forces (now the Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy) before another tour at Ft. Hood, which is where he learned he had made the list for brigadier general. It was an extraordinary step for the boy from Excelsior, who for many years was undecided about even staying in the Army, let alone becoming a general. Gray later was promoted to major general, marking another ground-breaking first as he became the Army’s first black JAGC officer to serve as either a one-star or two-star. As Gray’s Army career came to a close, he considered his options. “I could have returned to practicing law, of course. But a couple of things changed my thinking,” he said. “One was the law school classmate I often had lunch with who said an interesting thing to me. It was this: ‘Ken, you should do something that warms your heart.’ ” Meanwhile, one of Gray’s closest Army mentors had retired and gone to Clemson University as an administrator. “Working on a college campus appealed to me. I liked the idea of working with young people just starting their lives,” Gray said. Around the same time, Gray attended a brunch at WVU where he ran into University President David Hardesty. They chatted and, later, Gray and his wife were invited to a WVU football game. “I knew these kinds of events were often the setting for a job offer,” Gray said. “Nothing happened, though. First quarter, second quarter, halftime, game over—no offers tendered. But then I was walking down the stadium stairs with my wife, and coming down the stairs from just above was President Hardesty. We made some small talk. I told him a bit about my background. And a few days later I was invited to interview for a senior post at the university.”

Ken Gray has been vice president for student affairs at WVU since 1997, helping to steer a major university through changes and growth into the 21st century. Superlatives apply to this unique Vietnam veteran, a man of many career firsts, all of them historic. But Gray is quick to note that no achievement is reached alone or in a vacuum. “At every step of the way I’ve had help—from my parents, from teachers, from fellow soldiers and mentors and professional colleagues,” he said. “I’ve been very fortunate. And my wife, Carolyn, is my biggest asset. Because, do you know hard it is to be an Army spouse? I couldn’t have done any of it without her.” Ken Gray’s story is one of quiet bravery and focused effort, one in which racial barriers were met and passed as he opened a way for many others to follow, creating opportunities for individuals long locked out of the American Dream. It’s a narrative he shares with modesty, humor, and compassionate understanding. “I have just one more story to tell,” Gray told me. “When I was in law school my wife and I could not find an apartment in Morgantown. There were excuses made about why landlords wouldn’t help us, but we all understood the reasons to be what they were—race. So we decided to buy a trailer and went about looking for a space to put it. The first trailer park owner turned us down, telling us that if he rented to us he’d lose all his other customers. But he said he knew who could help. He called another trailer park owner, who rented us a space and gave us a place to live. And became a friend.” Ken Gray smiled. “I guess this story underscores my belief that people are often fundamentally good. We might be hemmed in by the times we live in, compelled for various reasons to do certain things we know aren’t really right. But there are a lot of charitable and generous people who struggle to do the right thing. Those two trailer park owners recognized the situation. They knew what was wrong about it, and one of them had the courage to act and help a struggling young couple.” When asked if the world is a better place since he was growing up in Excelsior, Gray said, “the brief answer is yes—things are better. I grew up in a segregated society. I was ten years old when Brown v. Board of Education was decided and the separate but equal doctrine was struck down. As a country, we have come a long way. I have been able to accomplish more during my lifetime than I ever thought possible. “Do we have more to do to solve the many problems that still exist? Yes. But I believe and I hope as a country we will continue to make progress toward equality for everyone.”

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||||

When Ken Gray came home from Vietnam in August 1971, he had every intention of getting out of the Army. He was a captain in the Army’s Judge Advocate General Corps coming off a tour with the Da Nang Support Command, and imagined he would do what many young lawyers did at that point: finish his service time and return to civilian practice.

When Ken Gray came home from Vietnam in August 1971, he had every intention of getting out of the Army. He was a captain in the Army’s Judge Advocate General Corps coming off a tour with the Da Nang Support Command, and imagined he would do what many young lawyers did at that point: finish his service time and return to civilian practice. “I had the opportunity to become the deputy staff judge advocate of the 1st Armored Division, based in Germany,” Gray said. “I realized that if I was going to get out of the Army, that was the time to do it.” But it was also clear that the opportunity was much more than simply another duty assignment—it clearly reflected the confidence that his colleagues and the JAGC had in his ability to lead and to embody the principles of diversity that had marked Gray’s career from the outset.

“I had the opportunity to become the deputy staff judge advocate of the 1st Armored Division, based in Germany,” Gray said. “I realized that if I was going to get out of the Army, that was the time to do it.” But it was also clear that the opportunity was much more than simply another duty assignment—it clearly reflected the confidence that his colleagues and the JAGC had in his ability to lead and to embody the principles of diversity that had marked Gray’s career from the outset.